What follows is the “patented” Lucy Shelton Pitch Chart Method for learning nonharmonic, 12-tone, or just plain hard vocal music. I learned the system in 2003 at Tanglewood while working on Dallapiccola’s 12-tone Four Lyrics of Antonio Machado. (For my non-musician readers: “12-tone” music is based on a pattern, or a “row,” of notes that uses all 12 tones of the scale before repeating pitches. This pattern can be presented in many permutations: chopped up, backwards, turned around, etc..) When I was learning the music, at home before getting to Tanglewood, I really sweated over the score. How was I supposed to get these “melodies” to stick in my head?! Especially when my line often clashed in unexpected ways with the piano. I was really nervous. Was this going to be the first impression I made at Tanglewood, not knowing my notes?!

At my first coaching with Lucy, she put all my fears to rest. There was something almost mystic about the way this system takes the “impossible” and makes it not only accessible, but a delight to learn. Here’s how it works.

The basic idea is to separate the notes completely from the rhythm and text. In order to do this, get some blank manuscript paper (paper with music staves on it). Taking one phrase at a time, write each note of your vocal line as a whole note. If there is a key signature, keep it in mind as you write, adding the appropriate accidental to each note. (So, there will be no key signature on the staff itself.) When the melody line gets extreme, high or low, write the note in two octaves so you can practice the line with octave displacement. (This saves vocal resources in those early days of learning the notes.)

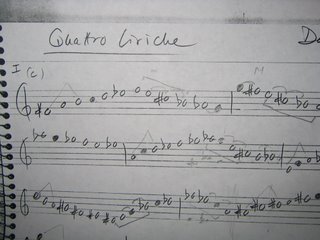

The basic idea is to separate the notes completely from the rhythm and text. In order to do this, get some blank manuscript paper (paper with music staves on it). Taking one phrase at a time, write each note of your vocal line as a whole note. If there is a key signature, keep it in mind as you write, adding the appropriate accidental to each note. (So, there will be no key signature on the staff itself.) When the melody line gets extreme, high or low, write the note in two octaves so you can practice the line with octave displacement. (This saves vocal resources in those early days of learning the notes.) Now, choose one pitch to serve as a pedal tone. This should be the note, if there is one, that is something of a tonal center, a pitch you return to or center around throughout the piece. (For 12-tone, Lucy suggests simply starting with C.) Play this pedal tone in several octaves, sustaining it while you sing or whistle or hum through the vocal line. Pay attention to each notes relationship to the pedal; this is the key. For example, in the photo above, you’ll see the first few phrases of the first Machado song. Using C as my pedal tone, I would find the F# by hearing the tri-tone relationship to the C, find the A in relationship to the F# and the C, etc.. My favorite moments in this process are when you sing a half-step below or above the pedal tone and then resolve, as the Machado does in that first phrase (B to C). For music like this that has no “home” pitch, like tonal music does, this feeling of arrival is beautiful.

After you have worked through the vocal line a few times with one pedal tone, choose a new one. Find the second-most predominant tone, or use G for 12-tone. Go through the process again, hearing how the “melody” changes in this new context. Honestly, I find it beautiful.

As you’re working through the piece, also look for relationships within the line itself. Where are the major 4ths and 5ths? (You can see them indicated above by the triangular or bracketed lines.) Where are the traditionally scalar passages? Half-steps?

Work with the pitch chart exclusively for as long as possible!! Things like rhythm and language are much easier to incorporate, generally, than these unfamiliar melodic structures. Keep the manuscript paper with you and study whenever you have a moment, in the waiting room of the Social Security Office, for example. When working like this, without a piano for pedal tones, it basically becomes an exercise in sight-reading, focusing on the relationships of each note to the next. But always remember the pedal, and see if you can “hear” it as you work, coming “home” to it in your mind’s ear. An easy way to study like this, when out in public, is to plug one ear closed with your finger and lightly “whistle.” This works especially well on an airplane: you’re able to hear yourself clearly and not annoy your neighbors. And, again, it’s a good vocal resources conserver! No need to drill these notes at full voice for hours on end.

I think that’s it. Clear as mud? Please leave a comment if you have any questions, and I’ll try to clarify. Writing this all out makes me wish I had some atonal music to learn!!

Happy studying.

6 comments:

I really admire you young opera singers - you are so well versed on musical matters - much more so than I was when taking singing lessons in the late 1940-s & 50's. Keep it up.

WOW!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Love it, love it, love it.

Thank you! I think the worst part may be hand-copying the notes from the score :P

Another approach I've tried is harmonically analyzing groups of 3 or 4 consecutive notes as a chord. You then learn the "melody" as a really wacky chord progression.

This is a great approach, and I admire you for being willing to go to the extra trouble. For your pedal note to work against, I'd suggest looking to the accompaniment for something to work with.

My concern about boston_soprano's approach is that she might be in trouble when faced with the real accompaniment, as opposed to the wacky chord progression.

Michael

Composer and solfège nerd

This post came into my head as I'm trying to learn fourth position on cello - trying to slide back into another hand position you really have to just 'know' where to land. Thinking about the notes I'm landing on and humming them as I come up to them, thinking about their relation to the tonic, etc etc has really made a difference.

So thanks for the post!

I have a question about this. I have kept this post of yours in the back of my mind knowing that it would come in handy some day and that day has arrived, as I am trying to learn some Crumb. Do you write the pitches of each phrase in they order that they appear in the score or as an ascending/descending line, as your photo indicates. Or was that just the order that pitches came? I really appreciate your post on this, even though it was forever ago. It seems to take the fear out of learning music like this.

Post a Comment